Building a 4-Microsecond HFT Engine for Crypto Arbitrage

How I optimized a strategy from milliseconds to microseconds using C++, Pybind11, and Order Book Imbalance.

In High-Frequency Trading (HFT), a millisecond is an eternity. It’s the difference between being a "maker" providing liquidity and a "taker" paying fees on a stale price.

When I started designing my crypto arbitrage strategy, I did what everyone does: I opened a Jupyter Notebook. I loaded tick data into Pandas, calculated signals using vectorized operations, and felt productive. But then I hit a wall.

Vectorized backtesting is great for research, but it suffers from Look-Ahead Bias. To simulate a real trading environment, you need an Event-Driven system, one that processes the market tick-by-tick, just like a live exchange feed.

When I tried to run a true event-driven loop in pure Python over millions of trades, the performance was unacceptable. The latency per tick was hovering around 1-2 milliseconds. In the crypto markets, where price discovery happens in microseconds, my "fast" Python bot was a dinosaur.

I realized that to build a portfolio-worthy engine, I needed the best of both worlds: the ease of Python for data analysis and the raw speed of C++ for execution.

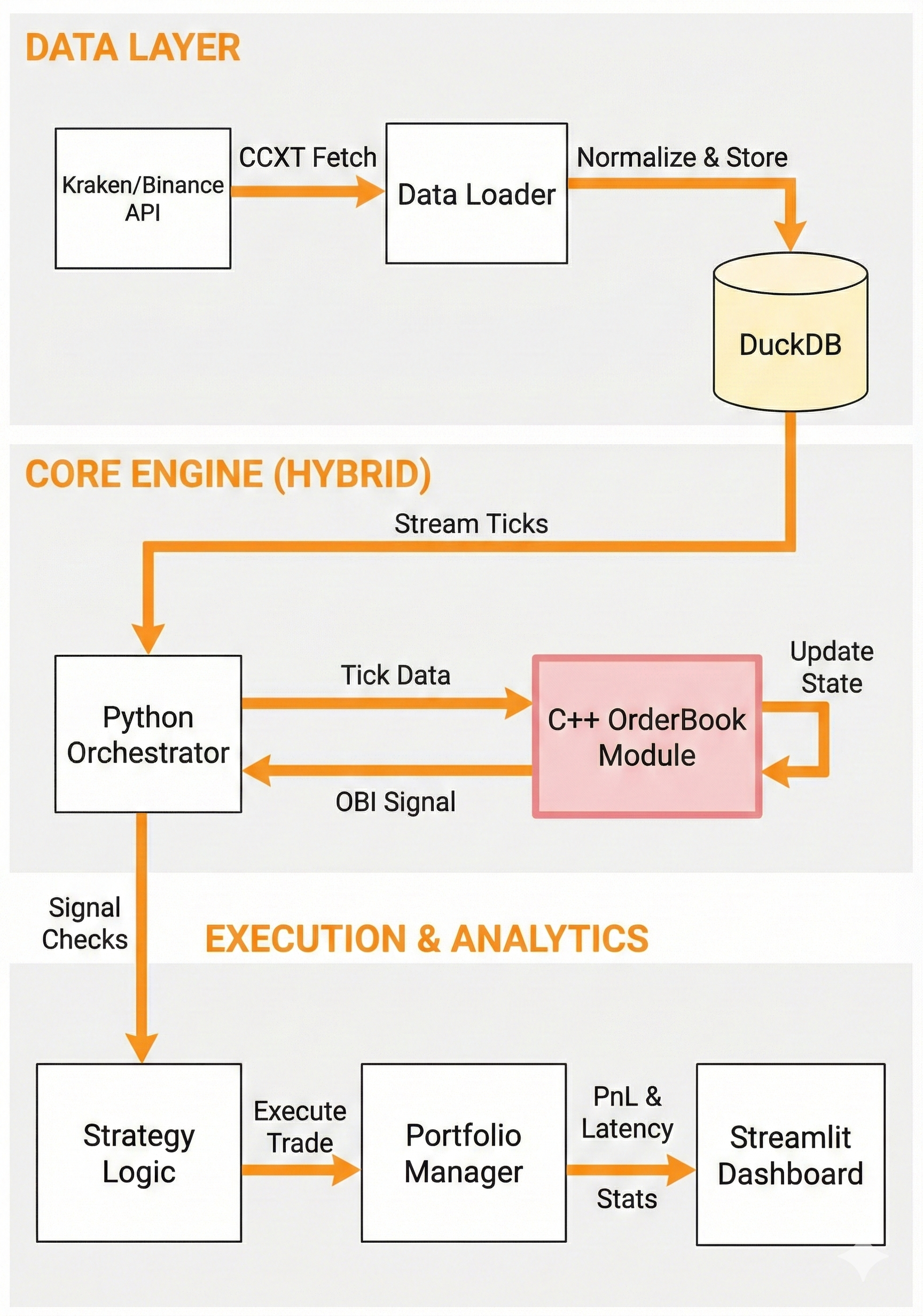

The Architecture: A Hybrid "Ferrari" Engine

I redesigned the system with a clear separation of concerns. I call it the "Hybrid Core" architecture.

-

The Brain (C++17): I wrote the OrderBook logic and signal processing in C++. By using

std::unique_ptrand memory-aligned structures, I minimized cache misses. This module handles the heavy lifting: reconstructing the limit order book and calculating imbalances. - The Orchestrator (Python): I kept Python for what it does best—Data Engineering (ETL) and Visualization.

-

The Bridge (Pybind11): This was the game-changer.

pybind11allowed me to expose my C++ classes to Python with zero-copy overhead.

The result? I could feed a tick from Python to C++, update the state, calculate a signal, and return the decision in ~4.5 microseconds. That is 400x faster than my original pure Python implementation.

The Logic: Exploiting Microstructure

Speed is useless without a strategy. I focused on Latency Arbitrage between correlated assets: Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH). The hypothesis is simple: Bitcoin leads, Ethereum follows.

When a massive buy order hits Bitcoin, arbitrage bots will eventually correct Ethereum's price upwards. There is a tiny window of time where BTC has moved, but ETH hasn't yet. To detect this, I measure the Order Book Imbalance (OBI) of the Leader (BTC):

If OBI > 0.3: Buyers are aggressively lifting the offer on BTC. Action: Buy ETH immediately.

If OBI < -0.3: Sellers are hitting the bid on BTC. Action: Short Sell ETH immediately.

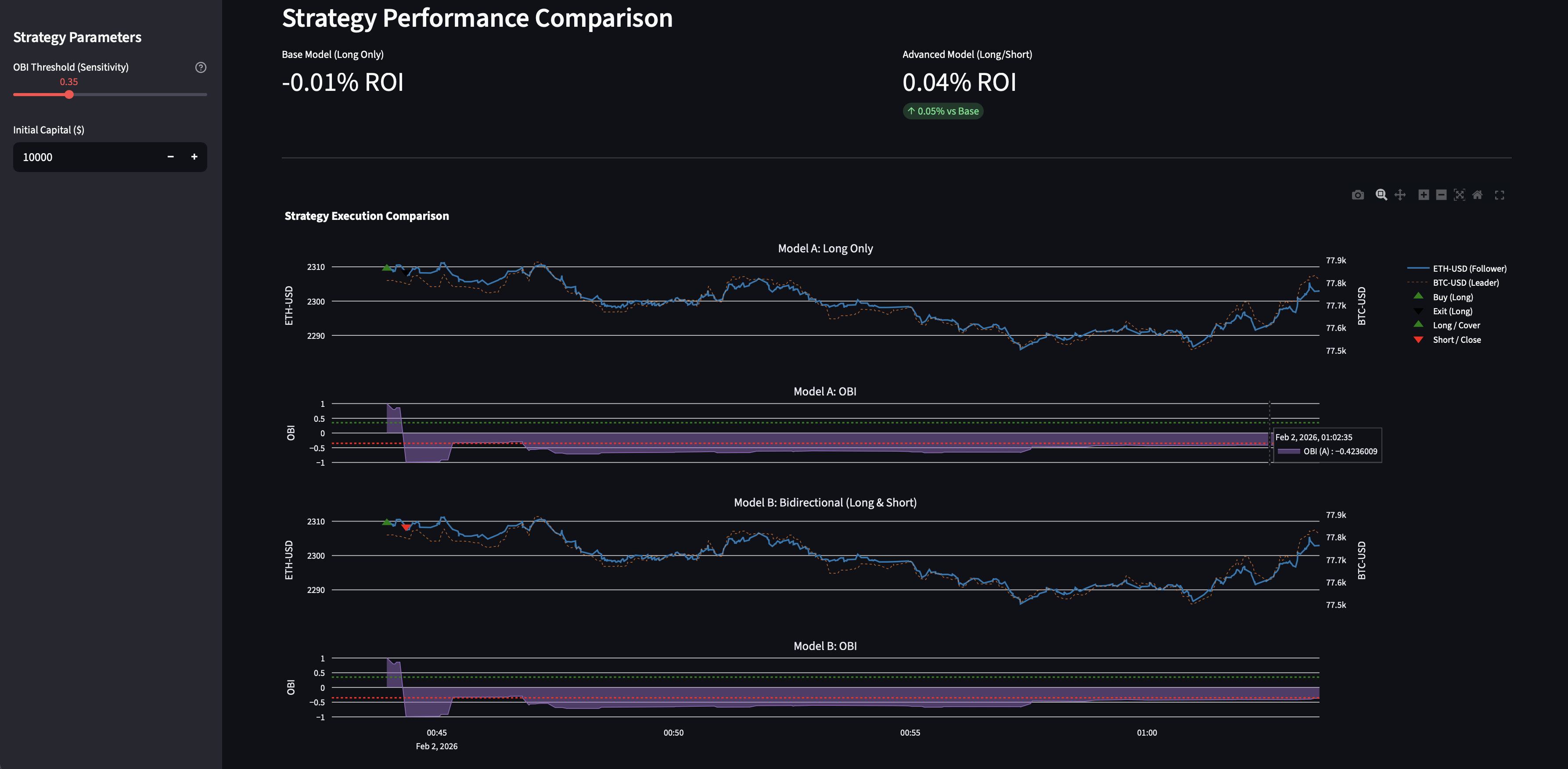

Visualizing the Alpha

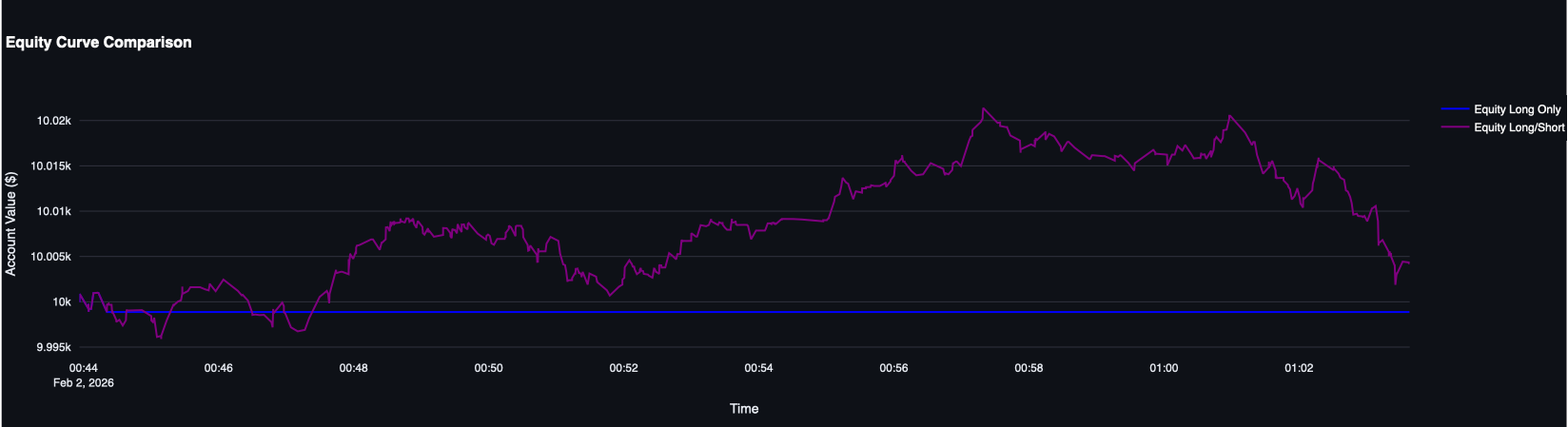

Numbers in a terminal are dry. I built a custom Streamlit Dashboard to visually verify the "Causality" of the signals. In the chart above, you can see the "Flip" Mechanism in action during a market crash.

Unlike a basic "Long Only" bot that sits on its hands during a crash, my engine executes a Position Reversal. It sells the existing Long position and immediately opens a Short position. This allows the equity curve to rise even while the market bleeds.

Lessons Learned

Building this engine taught me three critical engineering lessons that you don't learn in a bootcamp:

- Memory Management Matters: In Python, the Garbage Collector handles everything. In C++, a memory leak in a high-frequency loop crashes your system in seconds. Using smart pointers was non-negotiable.

-

The "Zero-Copy" Rule: Passing data between Python and C++ can be slow if you copy memory. Learning to use pointers and references via

pybind11was key to keeping latency under 5µs. - Visual Debugging: A backtest can lie. Building the dashboard showed me bugs in my logic (like the "Exit on Neutral" issue) that I would have never found just by looking at the final ROI number.

"This project started as an attempt to speed up a loop and ended as a full-stack engineering challenge."

It bridges the gap between Quantitative Research and Systems Engineering. The code is open-source and available on my GitHub. If you are interested in HFT architecture or C++ optimization, feel free to check it out.